Key Points

- Research suggests that while AI can generate inventive outputs, current U.S. and global patent laws predominantly require human inventors, limiting AI to a tool role rather than granting it independent inventorship status.

- Evidence leans toward the need for broader policy analysis, as courts worldwide have largely rejected AI as an inventor in cases like DABUS, highlighting a gap between technological capabilities and legal frameworks.

- Industry leaders, such as those from Google, Microsoft, and IBM, emphasize patenting AI-assisted innovations to drive commercialization, but express concerns over potential patent floods and ownership complexities if AI inventorship were recognized.

- Thought leaders are divided: some argue recognizing AI inventorship could accelerate innovation and disclosure, while others warn it might undermine human incentives and lead to market distortions.

- It seems likely that without policy evolution, AI’s role could stifle certain R&D investments, though empathetic views acknowledge benefits for democratizing creativity across stakeholders.

Current Legal Landscape

In the United States, the USPTO’s 2024 guidance clarifies that AI-assisted inventions are patentable only if a natural person significantly contributes to the conception of the invention. This aligns with court rulings like Thaler v. Vidal (2022), affirming that only humans can be inventors under the Patent Act. Globally, similar rejections have occurred in the UK, EU, and Australia, though South Africa allowed a DABUS patent on formality grounds. As of 2025, no major shifts have occurred, with AI remaining ineligible as an inventor in key jurisdictions.

Implications for Innovation

Granting AI inventorship could democratize access to advanced tools, boosting efficiency in fields like drug discovery and materials science. However, it raises risks of over-patenting, where AI’s speed floods systems, complicating enforcement and increasing litigation. Industry perspectives highlight economic growth potential, with AI adoption linked to firm expansion and employment gains, but caution against monopolization by tech giants.

Policy Considerations

Broader analysis is essential to balance incentives: recognizing AI could encourage disclosure over secrecy, but maintaining human-centric rules preserves accountability. Stakeholders, including corporate leaders, stress adapting standards like non-obviousness to AI’s capabilities.

As a legal scholar specializing in U.S. intellectual property law, I find the provided statement to be a timely and accurate reflection of the evolving discourse on AI inventorship. The assertion that “the time has now come to assess” AI’s potential for inventorship is well-supported by recent judicial decisions, scholarly debates, and policy discussions, yet it correctly identifies a persistent gap in comprehensive policy analysis. Below, I critically examine this statement through the lens of the latest literature, drawing on 2024-2025 sources including USPTO guidance, academic articles, and insights from industry and thought leaders. This analysis highlights the statement’s strengths in capturing global momentum while underscoring its call for broader implications, such as innovation incentives, economic impacts, ethical concerns, and systemic challenges to the patent framework.

To begin, the statement’s reference to AI’s “ability to generate inventive outputs” aligns with empirical evidence of AI’s transformative role in invention processes. For instance, generative AI has accelerated discoveries in materials science, leading to a 44% increase in new materials, a 39% rise in patent filings, and a 17% uptick in product prototypes among researchers using AI tools. This capability is not hypothetical; AI systems like AlphaFold have enabled Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs in protein structure prediction, demonstrating how AI can produce outputs that meet traditional patent criteria of novelty, non-obviousness, and utility. However, the statement’s emphasis on assessment is apt because, despite these advancements, legal systems remain anchored in anthropocentric definitions of inventorship. Under U.S. law, as reaffirmed in the USPTO’s February 2024 Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions, only natural persons can be inventors, with AI treated as a tool requiring significant human contribution for patentability. This guidance specifies that inventorship focuses on human “conception”—the mental formation of a complete idea—evaluated via factors like contribution quality and relevance, without bright-line tests. Examples in the guidance illustrate scenarios: a human merely prompting an AI for an obvious solution does not qualify as invention, but designing or training an AI for a specific problem may.

Globally, the matter has indeed “reached courts,” as noted in the statement. The DABUS cases, spearheaded by thought leader Stephen Thaler, have tested AI inventorship across jurisdictions. In the U.S., UK, EU, and Australia, courts rejected AI as an inventor, emphasizing that patent laws require a “natural person” with legal personality, consciousness, and ownership capacity. South Africa’s 2021 allowance of a DABUS patent was procedural rather than substantive, not setting a precedent. These rulings, spanning 2022-2025, underscore the statement’s point on “wider scholarly and policy attention.” Scholarly works, such as a 2025 article in the Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, argue for recognizing AI inventorship to align patent law with its core purpose of promoting innovation, regardless of the process. The authors contend that excluding AI undermines incentives, encourages concealment of AI’s role, and discourages public disclosure, potentially leading to trade secret reliance over patents. Conversely, a 2024 CSIS analysis maintains that the current human-centric system suffices, warning against changes that could blur accountability lines.

The statement’s identification of a “significant gap” in broader policy analysis is particularly incisive. While courts and agencies like the USPTO have addressed immediate inventorship questions, deeper policy implications remain underexplored. For example, a 2024 Southern California Law Review symposium article examines how AI-generated inventions could overwhelm patent offices with surges in applications, akin to past DNA patent booms, leading to backlogs and “patent thickets”—overlapping rights that hike litigation costs and stifle follow-on innovation. Policy recommendations include using AI for examination, shifting prior art searches to applicants, and imposing portfolio limits to prevent concentration among tech giants. Thought leaders like Ryan Abbott (involved in DABUS litigation) advocate for AI recognition to foster transparency and update standards like non-obviousness, potentially redefining the “person having ordinary skill in the art” (PHOSITA) to include AI-assisted benchmarks. Others, such as Dan Burk, highlight AI’s current limitations, arguing against premature reforms.

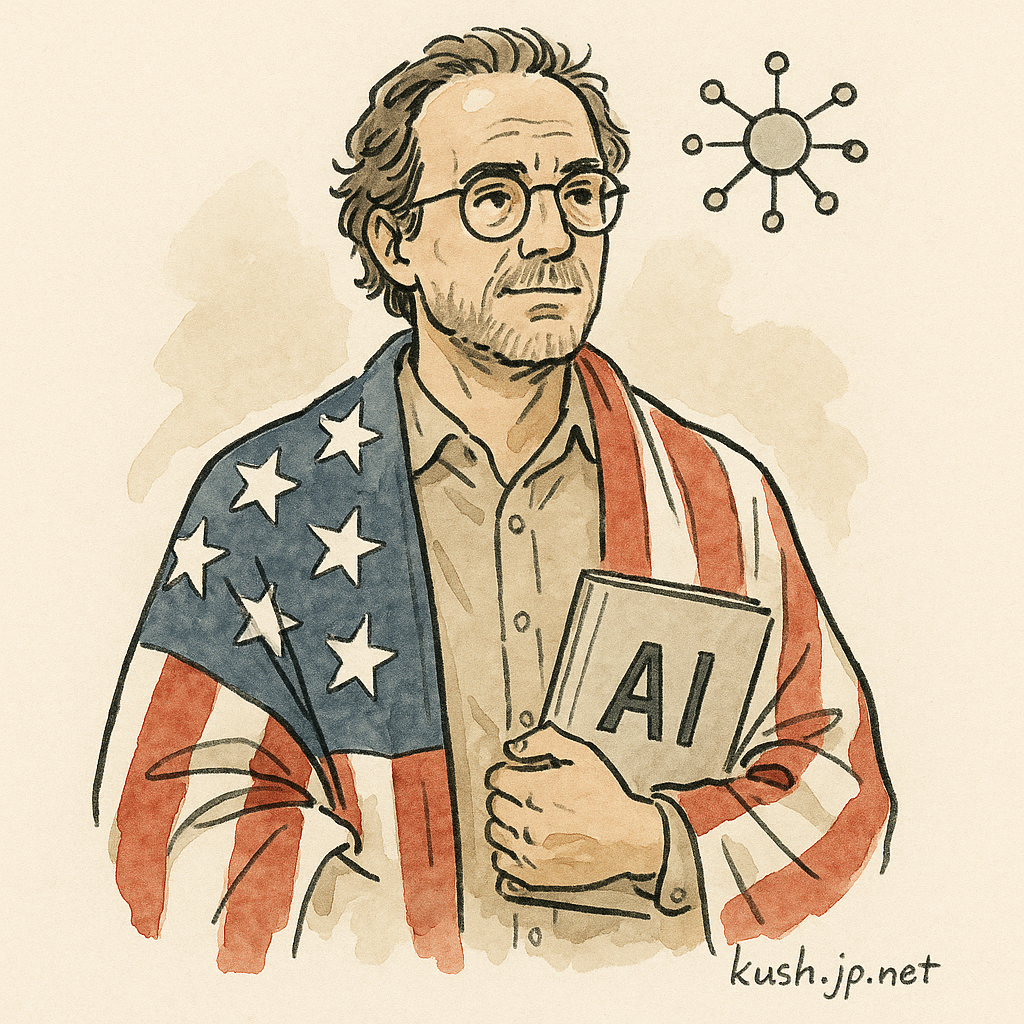

Turning to broader implications from industry leaders, tech behemoths like IBM, Google, and Microsoft dominate AI patent filings—IBM led with over 1,500 generative AI applications in 2023, followed by Google and Microsoft—but their stances on AI inventorship emphasize human oversight to secure protections. Google’s shift to lead in generative AI patents by 2025 reflects a focus on commercialization, with leaders viewing AI as a democratizing force that enhances human creativity without needing independent inventorship. Microsoft and OpenAI collaborations highlight concerns over co-inventorship risks, where AI developers could inadvertently become unwanted joint inventors, complicating ownership. Industry comments to the USPTO in 2023 stressed protecting AI inventions to encourage disclosure, but without granting AI legal personality, to avoid liability voids. For instance, at a 2025 LexisNexis webinar, experts from Meta, Google, and Adeia discussed using AI for fairer patent licensing, noting data analytics’ role in negotiations but cautioning on inventorship disputes.

Thought leaders provide a nuanced critique. Ethan Mollick’s 2024 analysis shows AI boosts top performers by 80% in output while aiding underperformers less, suggesting it amplifies inequalities rather than equalizing them. Benjamin Todd echoes this, noting AI’s role in idea generation but humans’ edge in evaluation. In policy circles, WIPO’s 2024 Patent Landscape Report on Generative AI reveals over 54,000 GenAI inventions filed from 2014-2023, with rapid growth, but dominated by Chinese firms like Tencent and Baidu, raising geopolitical implications for U.S. leadership. Leaders like Luiza Jarovsky highlight GenAI’s span across sectors, from life sciences to telecommunications, urging harmonized global policies. Critical voices, such as in a 2025 Brookings report, advocate for balanced views, noting AI’s potential to drive economic growth but warning of employment shifts and the need for counterarguments in controversial debates.

To organize key perspectives, consider the following table comparing arguments for and against AI inventorship:

| Perspective | Arguments For AI Inventorship | Arguments Against AI Inventorship | Key Proponents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Incentives | Promotes disclosure over secrecy; accelerates R&D in fields like drug discovery by incentivizing AI development. | Risks over-patenting and thickets, reducing follow-on innovation; current system suffices with human contributions. | For: Ryan Abbott; Against: USPTO, CSIS |

| Economic Impacts | Democratizes creativity, boosting firm growth and employment; addresses innovation slowdowns. | Could concentrate power among tech giants like Google/IBM, leading to monopolies; increases litigation costs. | For: Industry leaders (e.g., Microsoft); Against: Academic economists |

| Ethical/Legal Concerns | Aligns with patent law’s focus on outputs, not processes; prevents concealment of AI roles. | AI lacks consciousness/legal personality; blurs accountability and ownership. | For: Stephen Thaler; Against: Courts (DABUS rulings) |

| Policy Adaptations | Enables updates to standards like non-obviousness; facilitates global harmonization. | Avoids TRIPS violations; use AI for examination efficiency instead. | For: WIPO reports; Against: EPO/USPTO guidance |

In conclusion, the statement effectively captures the urgency for assessment amid judicial and scholarly progress, but the gap in policy analysis persists, as evidenced by ongoing debates. Broader implications include enhanced innovation versus systemic risks, with industry leaders prioritizing human-AI collaboration and thought leaders calling for adaptive reforms. Future policy must balance these to sustain U.S. competitiveness.

Key Citations

- Federal Register – Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions

- PMC – Why We Should Recognize AI as an Inventor

- CSIS – When AI Helps Generate Inventions, Who Is the Inventor?

- Southern California Law Review – AI-Generated Inventions: Implications for the Patent System

- WIPO – Patent Landscape Report on Generative AI

- IFI Claims – IBM Leads in GenAI Patents

- USPTO Comments on AI and Inventorship

- Novagraaf – AI Assisted Inventions

- Sterne Kessler – AI Inventorship: Navigating Patent Rights Around the Globe

- Reuters – How Artificial Intelligence Will Naturally Affect Patentability