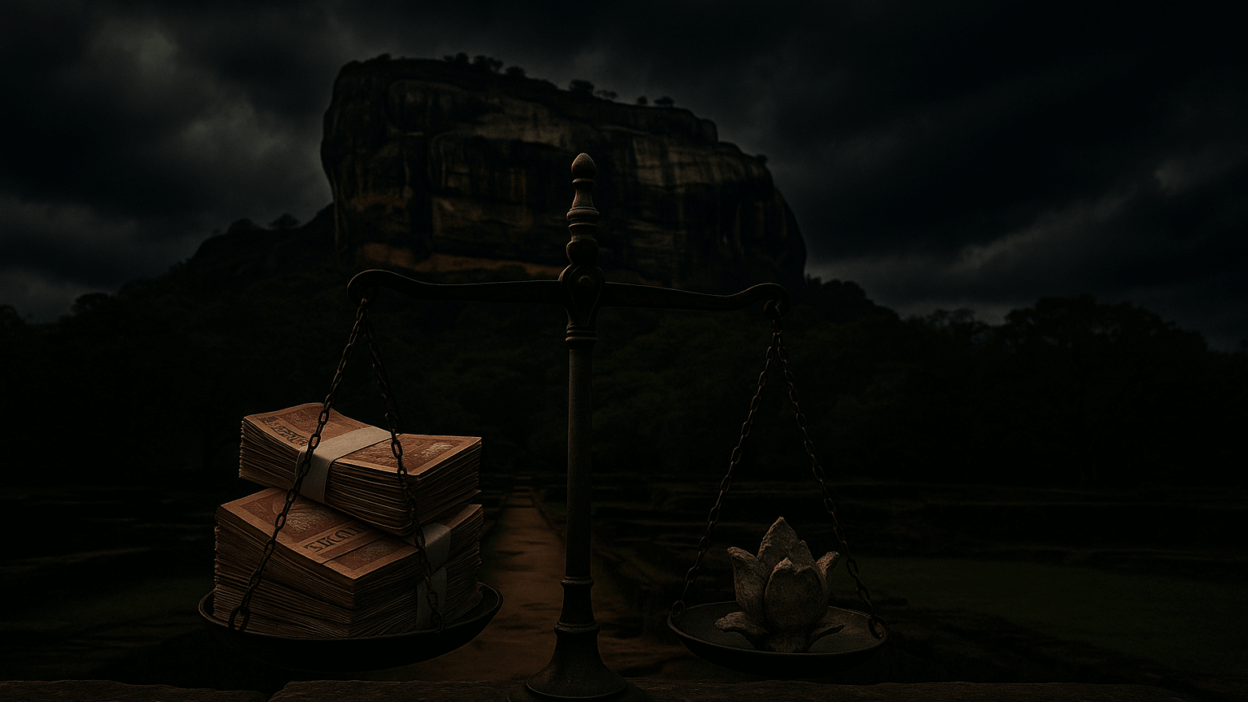

This report provides a comprehensive, multi-source investigation into the alleged financial irregularities and misappropriation of funds at Sri Lanka’s Central Cultural Fund (CCF) for the period of 2016 to 2019. The analysis synthesizes findings from official government inquiries, national audit reports, parliamentary oversight committees, and extensive media coverage to present a neutral and evidence-based assessment of a complex public finance controversy.

The core of the allegations stems from a 2020 committee report, chaired by retired High Court Judge Gamini Sarath Edirisinghe, which claimed financial misappropriation and losses at the CCF amounting to approximately Rs. 11 billion. The Edirisinghe Committee detailed a range of irregularities, including unauthorized withdrawals from fixed deposits, unapproved donations to religious institutions, excessive staff recruitment, and a specific withdrawal of Rs. 400 million during the 2019 Presidential Election campaign. These explosive findings were made public just one week prior to the 2020 Parliamentary General Election, implicating the then-Minister of Cultural Affairs, Sajith Premadasa, and making the issue a focal point of intense political debate.

However, the Edirisinghe Committee’s findings do not exist in a vacuum. They are corroborated and contextualized by a series of highly critical reports from Sri Lanka’s Auditor General’s Department covering the same period. These audits reveal a pattern of chronic, systemic weaknesses in financial controls, non-compliance with government regulations, and a profound lack of transparency at the CCF. The Auditor General’s decision to issue a “Disclaimer of Opinion” on the CCF’s financial statements for both 2018 and 2019—the most severe finding possible—independently confirms a state of institutional chaos that made proper financial accountability impossible.

In his defense, then-Minister Premadasa did not dispute the expenditures but reframed them as necessary and justifiable actions taken for national development and religious upliftment, particularly in the aftermath of the 2019 Easter Sunday terrorist attacks. He characterized the investigation as a politically motivated smear campaign designed to damage his electoral prospects.

Despite the gravity of the allegations, the legal and institutional aftermath has been inconclusive. There is no public record of a comprehensive criminal investigation or prosecution related to the headline Rs. 11 billion figure. Subsequent parliamentary scrutiny by the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) focused on narrow procedural issues, such as the potential forgery of signatures on a single board meeting document. The persistence of the controversy is evidenced by the appointment of yet another investigative committee in 2025 to re-examine the period. This cycle of investigation without legal resolution suggests that the CCF affair serves as a case study in the weaponization of accountability mechanisms for political leverage, highlighting enduring weaknesses in Sri Lanka’s public finance governance.

1. Background: The Central Cultural Fund and the Political Milieu

1.1. Mandate and Financial Structure of the CCF

The Central Cultural Fund (CCF) was established by the Central Cultural Fund Act, No. 57 of 1980, as a body corporate with a mandate to raise funds for the development, restoration, and preservation of Sri Lanka’s cultural and religious monuments.1 Its primary focus has been on the archaeological sites within the area designated as the “Cultural Triangle,” which includes the ancient cities of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Kandy, along with other key heritage sites like Sigiriya and Dambulla.1

The CCF’s financial structure is a critical element in understanding the subsequent controversy. Unlike typical government departments that are wholly dependent on annual allocations from the national Treasury, the CCF possesses significant financial autonomy. Under its establishing act, the Fund is empowered to receive government grants, private donations, and, most importantly, to generate its own revenue.1 A substantial portion of its income is derived from the sale of entrance tickets to foreign tourists visiting UNESCO World Heritage Sites, making it a major earner of foreign currency.2

This financial independence, designed to ensure a dedicated and consistent funding stream for heritage conservation, also created a large and flexible pool of capital under the direct purview of its governing board and the responsible government minister. The CCF’s Board of Governors, which is tasked with approving investments and expenditures, is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes several cabinet ministers and senior public officials.1 This structure inherently places a politically valuable financial asset under the discretionary control of the executive branch, creating a system vulnerable to being co-opted for projects that offer greater political visibility than its core, long-term archaeological mandate.

1.2. The Political Landscape (2016-2019)

The period under investigation, 2016 to 2019, coincided with the tenure of the ‘Yahapalanaya’ (Good Governance) coalition government. This government was characterized by a fragile power-sharing arrangement and significant internal tensions, particularly between the two main coalition partners. Sajith Premadasa, a prominent figure in the United National Party (UNP), served as the Minister of Housing, Construction, and Cultural Affairs, which placed the CCF directly under his ministerial oversight.5

The political context was further complicated by an emerging rivalry within the UNP between then-Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and Premadasa. This rivalry intensified in the lead-up to the November 2019 Presidential Election, when Premadasa successfully challenged Wickremesinghe for the party’s presidential nomination.5 It is noteworthy that the first inquiry into alleged financial mismanagement at the CCF, concerning a sum of Rs. 1.2 billion, was ordered by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe during this period of intense intra-party competition, though the results of that probe were never publicly revealed.5 This history indicates that the financial activities of the CCF were politicized even before the change of government and the appointment of the Edirisinghe Committee.

2. The Edirisinghe Committee Report: Allegations of an Rs. 11 Billion Misappropriation

2.1. The Committee’s Mandate and Composition

Following the 2019 Presidential Election and the subsequent change in government, the new administration under Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa initiated a formal investigation into the CCF’s activities. In January 2020, a three-member committee was appointed to probe financial irregularities and misappropriation at the Fund for the period from 2016 to 2019.6

The committee was chaired by Gamini Sarath Edirisinghe, a retired High Court Judge, and included Gotabaya Jayaratne, a former cabinet ministry secretary, and Harigupta Rohanadeera, an Attorney-at-Law.2 This composition was intended to lend judicial and administrative weight to its findings. The committee submitted its 142-page report to Prime Minister Rajapaksa on July 28, 2020.5

2.2. A Forensic Breakdown of Alleged Financial Losses

The central finding of the Edirisinghe Committee Report, as communicated to the public through a statement from the Prime Minister’s Office, was that the CCF had incurred losses and seen funds misappropriated to the value of Rs. 11,059 million (approximately Rs. 11 billion) between 2016 and 2019.2 While the full report has not been made public, media reports based on the official release provide a detailed breakdown of this headline figure.

The structure of these allegations combines verifiable procedural breaches with large, difficult-to-prove sums under headings like “misappropriation,” seemingly designed for maximum political impact. The specific, incendiary claim of a Rs. 400 million withdrawal during an election campaign serves as a political centerpiece, while more mundane procedural issues lend the report an air of detailed investigation. This blend creates a powerful political narrative that is difficult for opponents to rebut completely, as the underlying evidence of procedural sloppiness makes the entire narrative seem plausible to the public.

Table 1: Breakdown of Alleged Financial Misappropriation per the Edirisinghe Committee Report

| Alleged Irregularity / Loss Category | Amount (LKR Million) |

| Recruitment in excess of approved cadre (salary/bonus overheads) | 3,060 |

| Unauthorized withdrawal of fixed deposits & loss of interest | 2,608 |

| Spending without contributions to the Archaeological Trust | 2,316 |

| Unapproved cultural donations and contributions | 2,316 |

| Unauthorized spending on ‘Sisu Daham Sevana’ program | 753 |

| Unauthorized withdrawal during 2019 Presidential Election | 400 |

| Loss from encashment of traveller’s cheques / dollar conversion | 48 |

| Loss from handing over ‘Ape Gama’ project assets | 8 |

| Total (as per reported items) | 11,509 |

Note: The sum of the itemized figures reported in the media (Rs. 11,509 million) is slightly higher than the officially stated total of Rs. 11,059 million, indicating minor discrepancies in the public reporting of the committee’s detailed findings.

2.3. Findings on Administrative and Procedural Malpractice

Beyond the headline financial figures, the Edirisinghe Committee reported a series of grave administrative and procedural failures that pointed to a collapse of governance at the CCF.

- Unauthorized Financial Instruments: The committee found that the CCF had opened and maintained 25 current accounts without obtaining the necessary approval from the Treasury, a direct violation of state financial regulations.2

- Irregular Approvals: A key finding concerned a Board of Governors meeting allegedly held on November 15, 2019, just one day before the Presidential Election. The report claimed this meeting was convened to retroactively approve all improper expenses made during 2019. It further alleged that while only five members attended, the official record included the signatures of all absent members, leading the committee to question the document’s legality and recommend a verification of the signatures.2

- Election-Related Withdrawals: The report singled out an unauthorized withdrawal of Rs. 400 million from a CCF savings account during the 2019 Presidential Election campaign, a period when Sajith Premadasa was the candidate for the incumbent party.8 This was one of the most politically damaging allegations.

- Systematic Violations: The committee also cited the illegal release of funds from the CCF’s dollar-denominated account, the purchase of equipment in violation of fiscal policies, and the subsequent creation of documents to cover up these irregularities.2

3. The Auditor General’s Perspective: A Pattern of Systemic Weakness

The findings of the Edirisinghe Committee are powerfully contextualized by the official audits conducted by Sri Lanka’s Auditor General’s Department (AGD). These reports, which are technical and politically neutral, reveal that the CCF’s financial and administrative problems were chronic, systemic, and had been officially documented for years. The AGD’s work suggests that the Edirisinghe Committee did not uncover a secret scandal so much as it politicized and amplified a well-documented, ongoing institutional collapse that had been flagged repeatedly by the state’s own supreme audit institution.

3.1. Early Warnings: Key Findings from the 2016-2017 Audits

The AGD’s annual audit reports for the years preceding the most intense period of alleged malpractice already contained numerous red flags. The report for the year ended 31 December 2016, noted several of the same issues later highlighted by the Edirisinghe Committee, including:

- The opening of 25 bank current accounts without Treasury approval.4

- The granting of Rs. 79 million for cultural activities and donations without the required approval of the governing board.4

- A failure to adhere to a Cabinet decision requiring 25% of income from ticket sales (a sum of Rs. 861 million for 2016) to be given to the Archaeological Management Trust.4

- The failure to table annual reports for 2013, 2014, and 2015 in Parliament in a timely manner.4

The audit for 2017 continued to identify unresolved issues, such as unrecovered staff loans and improper accounting practices.13 These reports establish a clear baseline of poor governance and non-compliance with financial regulations that was deeply embedded in the CCF’s institutional culture.

3.2. A Red Flag: The “Disclaimer of Opinion” on the 2018 & 2019 Financials

The most damning evidence from the AGD came in its reports on the CCF’s financial statements for the years 2018 and 2019. For both years, the Auditor General issued a “Disclaimer of Opinion”.14 This is the most severe conclusion an auditor can reach. It signifies that the financial records and supporting documentation were so deficient, and the lack of evidence so pervasive, that it was impossible for the auditors to form an opinion on whether the financial statements presented a true and fair view of the Fund’s financial position.14

This finding represents a complete breakdown of basic public financial management. The AGD cited its inability to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence for vast sums of money, including documentary proof for fixed deposit investments valued at over Rs. 6 billion, various loan and advance accounts totaling hundreds of millions of rupees, and the fixed asset register.14 This independent, technical assessment provides powerful corroboration for the Edirisinghe Committee’s claims of chaotic, non-transparent, and unaccountable financial management.

3.3. Case Study in Irregularity: The Audit of the ‘Sisu Daham Sevana’ Program

The ‘Sisu Daham Sevana’ program, which aimed to construct buildings for Dhamma schools (institutions for Buddhist religious education), was a flagship initiative under Minister Premadasa and a key subject of the allegations. The AGD’s operational audit report for 2020, which reviewed activities from 2019, provided a detailed and neutral assessment of its implementation.16

The audit found multiple, clear violations of government procurement guidelines:

- The total estimated value of the project was Rs. 1,140 million, far exceeding the Rs. 250 million threshold that requires procurement to be handled by a Cabinet Appointed Procurement Committee. The CCF failed to follow this mandatory procedure.16

- Construction works were assigned to state-owned enterprises such as the State Engineering Corporation under a “direct contract system,” which contravened procurement guidelines requiring competitive bidding.16

- The program was expanded from 332 to 368 buildings, requiring a total allocation of Rs. 1,282.2 million, which exceeded the approved budget by Rs. 142.2 million.16

In its official response included within the audit report, the CCF management acknowledged the procedural deviations, stating that a Cabinet Memorandum had been submitted in 2019 to address the matter.16 This serves as an admission of non-compliance with established financial regulations.

4. The Minister’s Position: Defense and Counter-Allegations

4.1. The Allegations Against Minister Sajith Premadasa

As the minister with direct oversight of the CCF during the 2015-2019 period, Sajith Premadasa was the central political figure implicated by the Edirisinghe Report.5 The core accusation was that he had used the Fund’s substantial and autonomous financial resources to fuel a nationwide patronage network, providing donations and funding for religious projects in a manner designed to build his personal political image ahead of a presidential run.17

4.2. The Parliamentary Defense: Justifying Expenditures on Religion, Culture, and National Security

Premadasa mounted a robust defense against the allegations, most notably in a detailed speech in Parliament in September 2019, before the Edirisinghe Committee was formed but after initial accusations had begun to circulate.18 His defense did not deny the large-scale spending but sought to reframe it as a moral and nationalistic duty, effectively arguing that the ends justified the means.

He stated that Rs. 1,598 million had been withdrawn from the Fund’s deposits to cope with the severe drop in tourism revenue following the April 2019 Easter Sunday terrorist attacks, which had crippled a key income source for the CCF.3 He argued that these funds were essential for continuing the nation’s cultural development work.

He provided a lengthy and specific list of projects funded by the CCF under his tenure, emphasizing the cross-religious nature of the support. This included:

- The ‘Sisu Daham Sevana’ program to construct 361 Dhamma schools, with a target of 1,000.18

- Rs. 384 million for major Buddhist heritage sites like Mirisawetiya and Mihintale.18

- Rs. 50 million for the Thalawila Church and a “huge project” at the Madhu Shrine, both significant Christian pilgrimage sites.18

- Assistance for mosques that were damaged in the aftermath of the Easter attacks.18

He concluded his parliamentary address by asserting that every cent was spent for the benefit of “the Buddhasasana and other religions,” that all projects had received Cabinet approval, and that nothing had been misused.18 This defense reveals a fundamental tension in Sri Lankan governance between populist developmentalism and procedural propriety; by shifting the debate from “Was it legal?” to “Was it right?”, he appealed directly to the electorate’s values over the technocratic concerns of auditors.

4.3. The Public Defense: Framing the Investigation as a Political Smear Campaign

Outside Parliament, Premadasa and his political party, the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), consistently and forcefully rejected the allegations as a politically motivated attack. They characterized the Edirisinghe Committee investigation as a “project to sling mud at me” launched by the rival Rajapaksa government.19 The SJB issued a formal statement calling the report’s release a “political stunt” deliberately timed to discredit Premadasa just one week before the August 2020 General Election.21

Premadasa publicly challenged his accusers, vowing to tour the country to showcase the development projects completed with CCF funds.19 In a parliamentary debate in December 2023, he declared he was ready to resign immediately if any written proof emerged that he had used state funds for his own private use or for his political party’s activities.22 This challenge to prove personal enrichment was a strategic misdirection; the core allegation was the misuse of

public funds for political purposes (patronage), not personal theft. By setting this high bar, he could claim vindication while sidestepping the more substantive and well-documented allegations of gross procedural malpractice.

5. Aftermath and Accountability

The aftermath of the Edirisinghe Committee Report demonstrates how accountability processes in Sri Lanka can become political tools, where the goal is often sustained political pressure rather than legal resolution. The cycle of investigation, public disclosure, and institutional inaction suggests that accountability is frequently performed rather than delivered.

5.1. The Politics of Disclosure: The Report’s Release Before the 2020 General Election

The timing of the report’s release is impossible to ignore in any neutral analysis. The committee handed its report to the Prime Minister on July 28, 2020, and its findings were immediately publicized.5 The Parliamentary General Election was held on August 5, 2020, just eight days later. This timing ensured that the allegations against Sajith Premadasa, the leader of the main opposition party, dominated the news cycle in the final, critical week of the campaign, leading to widespread accusations that the report was being used as a political weapon.5

5.2. Parliamentary Oversight and the COPE Investigation

The parliamentary Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) subsequently launched its own inquiry, based not on the Edirisinghe Report but on the special audit report from the Auditor General covering 2015-2019.23 During a meeting on March 7, 2023, COPE focused on a narrow but highly specific irregularity: the validity of the 209th meeting of the CCF’s governing council.23

The Auditor General informed COPE that there were discrepancies with the signatures on the attendance list for this meeting, and that the then-Prime Minister’s Secretary (who was a board member) had confirmed he was not a party to such a meeting.23 This gave credence to the Edirisinghe Committee’s claim that approvals may have been improperly backdated or forged. COPE’s key recommendation was not to launch a broad investigation into the Rs. 11 billion figure, but to refer the signature list of this one meeting to the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and the Government Inspector for a forensic examination.23 This action gave the appearance of progress without tackling the politically contentious core allegations.

5.3. A Trail Gone Cold? The Status of Police and CIABOC Investigations

Despite the Edirisinghe Committee’s recommendation to institute legal action against those responsible, there is no evidence in the public domain of a comprehensive investigation being launched by the CID or the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC) into the full scope of the allegations.26 The only specific referral to law enforcement documented is the narrow COPE recommendation regarding the signature list.23

In June 2024, CIABOC separately informed the Speaker of Parliament that it had commenced an assets investigation into Sajith Premadasa covering the period 2017 to 2023.28 However, the available information does not explicitly link this probe solely to the CCF affair, and it appears to be a broader review under the new Anti-Corruption Act. The lack of a focused, public investigation into the Rs. 11 billion allegation suggests that after the 2020 election, the political will to pursue the matter dissipated.

5.4. The Unresolved Legacy: A New Committee for a New Era

The unresolved nature of the controversy was underscored in July 2025, when the Cabinet of Ministers approved the appointment of a new three-member committee, this time chaired by retired Supreme Court Judge G.M.W. Pradeep Jayathilake, to investigate irregularities at the CCF during the period from 2017 to 2020.17 The formation of a new committee to investigate largely the same period, five years after the first report, perpetuates the cycle of investigation without resolution and ensures the CCF affair remains a live issue in Sri Lanka’s political landscape.

6. Media Framing and Analysis

The media coverage of the CCF affair illustrates the highly polarized nature of Sri Lanka’s media environment, where outlets often act as amplifiers for competing political narratives rather than as independent arbiters of fact.

6.1. A Tale of Two Narratives: Comparing State-Aligned and Private Media Coverage

The release of the Edirisinghe Committee’s findings in July 2020 was met with starkly different frames. Media outlets aligned with the government, such as LankaWeb, reported the allegations as established facts. Their headlines declared, “Rs 11 bn. misappropriated at CCF under Yahapalana Govt.,” directly reflecting the government’s political messaging.9

In contrast, independent and private media outlets like the Daily FT and EconomyNext, while reporting the committee’s findings in detail, also provided crucial context. Their articles consistently noted the timing of the report’s release just before the election, included Sajith Premadasa’s history of denials, and mentioned the earlier, politically charged inquiry initiated by Ranil Wickremesinghe.2 This more nuanced coverage presented the public with a more complex picture, acknowledging both the allegations and the political maneuvering surrounding them. The SJB’s counter-narrative, which explicitly labeled the report a “political stunt,” was also given space in these outlets.21

6.2. The Impact of the Electoral Cycle on Journalistic Framing

The intensity and nature of the media coverage were heavily influenced by the electoral calendar. The initial wave of reporting in late July and early August 2020 was immediate, widespread, and politically charged, driven by the proximity of the general election.

After the election, sustained investigative follow-up into the allegations was noticeably absent. Media attention waned significantly, re-emerging only sporadically to report on procedural developments, such as the COPE meeting in 2023 or the appointment of the new committee in 2025.17 This pattern suggests a media cycle driven by political events and official pronouncements rather than a commitment to long-term investigative journalism to uncover the full truth of the matter. The public was thus presented with two conflicting “realities,” with their belief in either one likely determined by their prior political allegiance.

7. Conclusion: An Assessment of Evidence, Politics, and Institutional Failure

The controversy surrounding Sri Lanka’s Central Cultural Fund between 2016 and 2019 is a multifaceted issue that transcends simple narratives of corruption. It is a case study in the complex interplay of weak public financial management, political patronage, and the instrumentalization of accountability mechanisms in a deeply polarized political system.

7.1. Synthesizing Verified Irregularities and Unproven Allegations

A careful analysis of the available evidence leads to two distinct conclusions. First, there is substantial, credible, and politically neutral evidence from the Auditor General’s Department confirming that the CCF was plagued by systemic, severe, and long-standing failures in financial and procedural controls. The “Disclaimer of Opinion” for 2018 and 2019 is incontrovertible proof of institutional collapse, where basic standards of public accountability were not met.

Second, the Edirisinghe Committee Report took these documented institutional failures and packaged them with politically explosive but legally unproven allegations of large-scale misappropriation. While the committee’s findings on procedural violations are strongly supported by the AGD’s audits, its headline claim of an Rs. 11 billion misappropriation remains an allegation. It has not been tested or proven in a court of law, and the lack of any significant legal follow-up suggests it may have been intended more for political impact than for judicial reckoning.

7.2. The Interplay of Political Patronage and Public Finance Management

The CCF affair is a classic example of how state institutions with autonomous funding streams are acutely vulnerable to being used for political patronage. The defense offered by then-Minister Sajith Premadasa, which centered on the noble intentions of his projects, highlights a political culture that often prioritizes populist program delivery over adherence to legal and financial propriety. In this context, financial regulations are viewed not as essential safeguards for public funds, but as bureaucratic impediments to be bypassed in the service of a perceived greater good—a “greater good” that often aligns with the political objectives of the incumbent minister.

7.3. Enduring Weaknesses in Sri Lanka’s Governance and Accountability Mechanisms

Ultimately, the CCF saga reveals a failure across the entire chain of accountability. The Auditor General’s technical warnings were ignored for years by both the executive and parliamentary oversight bodies. A politically appointed committee was then used to weaponize these failures for electoral gain, only for its recommendations to be largely shelved after serving their political purpose. Key law enforcement and anti-corruption bodies failed to act decisively on the report’s findings. This sequence points to a systemic weakness in Sri Lankan governance, where the mechanisms of oversight are either too weak to enforce compliance or are captured and instrumentalized by political actors for partisan battles. The unresolved and cyclical nature of the CCF investigation is a symptom of a deeper malaise in the country’s public finance governance, where true accountability remains an elusive goal.

Sources

Official Reports and Government Publications

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Central Cultural Fund for the year ended 31 December 2016. http://www.auditorgeneral.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2016/funds_2016/3rd_ix-2016/Central-Cultural-Fund—E.pdf 1

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Central Cultural Fund for the year ended 31 December 2017. https://naosl.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2017/Funds/3_VIII/Central-Cultural-Fund—E.pdf 2

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Central Cultural Fund for the year ended 31 December 2018. https://www.naosl.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2018/funds_18/3-xx/Central-Cultural-FundE.pdf 3

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Central Cultural Fund for the year ended 31 December 2019. https://www.naosl.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2019/FUNDS_19/XXII/Central-Cultural-Fund–E.pdf 4

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Operational Activities of the Central Cultural Fund for the years 2018 and 2019. http://www.auditorgeneral.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2019/FUNDS_19/3_I/Central-Cultural-Fund–E—2018–2019.pdf 5

- Auditor General’s Department of Sri Lanka. Report on the Operational Activities of the Central Cultural Fund for the year ended 31 December 2020. https://www.naosl.gov.lk/web/images/audit-reports/upload/2020/Funds/3-xviii/Central-Cultural-Fund—E.pdf 6

- Cabinet Office of Sri Lanka. Press briefing of Cabinet Decision taken on 2025-07-07. https://www.cabinetoffice.gov.lk/cab/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=16&Itemid=49&lang=en&dID=13282 7

- Parliament of Sri Lanka. Central Cultural Fund Act, No. 57 of 1980. https://lankalaw.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ccf388271.pdf 8

- Parliament of Sri Lanka, Committee on Public Enterprises. Second Report of the Committee of Public Enterprises of the Fourth Session of the Ninth Parliament. https://www.parliament.lk/uploads/comreports/1696587095034241.pdf 9

Media Articles

- Ada Derana. Committee headed by judge to probe irregularities within Central Cultural Fund. (March 8, 2023). https://www.adaderana.lk/news/88925/committee-headed-by-judge-to-probe-irregularities-within-central-cultural-fund 10

- Ada Derana. Saijth says ready to resign if proven that he misused state funds. (December 6, 2023). https://www.adaderana.lk/news/95440/saijth-says-ready-to-resign-if-proven-that-he-misused-state-funds- 11

- Daily FT. Committee alleges Rs. 11 b misused at Central Cultural Fund. (July 29, 2020). https://www.ft.lk/News/Committee-alleges-Rs-11-b-misused-at-Central-Cultural-Fund/56-703838 12

- Daily FT. Sajith denies Central Cultural Fund misused. (September 5, 2019). https://www.ft.lk/News/Sajith-denies-Central-Cultural-Fund-misused/56-685197 13

- Daily FT. Three-member committee to probe irregularities in Central Cultural Fund. (July 9, 2025). https://www.ft.lk/news/Three-member-committee-to-probe-irregularities-in-Central-Cultural-Fund/56-778742 14

- Daily Mirror. Cabinet nod to probe irregularities at Central Cultural Fund. (July 8, 2025). https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/Cabinet-nod-to-probe-irregularities-at-Central-Cultural-Fund/108-313663 15

- DBSJeyaraj.com. SJB Leader Sajith Premadasa Says he Utilised the Central Cultural Fund to Uplift Buddhism… (October 3, 2022). https://dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/?p=79766 17

- EconomyNext. Probe finds misappropriation of funds in the Central Cultural Fund – Prime Minister’s office. (July 29, 2020). https://economynext.com/probe-finds-misappropriation-of-funds-in-the-central-cultural-fund-prime-ministers-office-72473/ 18

- Hiru News. THREE-MEMBER COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE CENTRAL CULTURAL FUND IRREGULARITIES. (July 9, 2025). https://hirunews.lk/goldfmnews/409549/three-member-committee-to-investigate-central-cultural-fund-irregularities 19

- InfoLanka. Release of CCF report a political stunt: SJB. (July 30, 2020). https://www.infolanka.com/news/2020/july/index46.html 20

- Lanka Sara. Committee to Probe Misuse of Central Cultural Fund During Sajith’s Tenure. (July 8, 2025). https://lankasara.com/news/committee-to-probe-misuse-of-central-cultural-fund-during-sajith-s-tenure/ 21

- LankaWeb. Rs 11 bn. misappropriated at CCF under Yahapalana Govt… (July 28, 2020). https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2020/07/28/rs-11-bn-misappropriated-at-ccf-under-yahapalana-govt-investigation-reveals-rs-400-mn-went-missing-during-presidential-election/ 22

- LankaWeb. Rs 11bn financial misappropriation at CCF from 2016 to 2019 – Report. (July 28, 2020). https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2020/07/28/rs-11bn-financial-misappropriation-at-ccf-from-2016-to-2019-report/ 23

- Parliament of Sri Lanka. COPE recommends to appoint a committee headed by a retired judicial judge to probe irregularities in the Central Cultural Fund. (March 8, 2023). https://www.parliament.lk/committee-news/view/3118 24

- Sunday Times. Cultural Fund pardons rowdy Russians for Tourism’s sake. (February 13, 2011). https://www.sundaytimes.lk/110213/News/nws_18.html 25

- Sunday Times (Online). Bribery Commission informs Speaker of assets investigation on Sajith. (June 5, 2024). https://sundaytimes.lk/online/news-online/Bribery-Commission-informs-Speaker-of-assets-investigation-on-Sajith/2-1145930 26

- Sunday Times (Online). Probe into Central Cultural Fund financial irregularities during yahapalanaya. (July 8, 2025). https://sundaytimes.lk/online/news-online/Probe-into-Central-Cultural-Fund-financial-irregularities-during-yahapalanaya/2-1149711 27

- The Morning. 2020 General Election: History in the making? (August 2, 2020). https://www.themorning.lk/2020-general-election-history-in-the-making 28

- The Morning. Sajith willing to tour country to disprove Cultural Fund allegations. (October 3, 2022). https://www.themorning.lk/sajith-willing-to-tour-country-to-disprove-cultural-fund-allegations 29

- The Morning. Unravelling ‘un’cultured spending. (August 2, 2020). https://www.themorning.lk/unravelling-uncultured-spending 30